It’s terrifying when the world around you starts to degrade, to disintegrate. When what once seemed irrefutably true shows itself to be false, the world – and the self – falter. We build lives on collectively held expectations, reassurances that what is will continue to be. But when our past reality ceases to exist, we are left with only questions: who am I in a world of uncertainty? And who am I becoming?

What happens when the system fails?

I sometimes think about the day Lehman Brothers declared bankruptcy. Bear Stearns’ collapse six months earlier might have been a fluke, a stroke of bad luck (or bad management). But Lehman’s fall was ominous: the first harbinger of system-wide failure on a global scale. It was impossible to know then exactly how the world was changing. But it seemed clear that a significant system-level transformation was taking place.

I had always felt an affinity with my Grandmother Marjorie, a connected understanding I couldn’t quite explain. Since her death, I’d wondered how I might tell her story, an urge that weighed on me almost constantly. In reading The Fourth Turning: An American Prophecy, I came to understand my connection to Marjorie more clearly. Written in 1997 by two sociologists, William Strauss and Neil Howe, The Fourth Turning analyzes centuries of western history to foretell a seismic transformation of society they suggested would begin sometime in the 2000s. The book is somewhat complex and arcane, which makes it both hard to summarize or recommend, but in this sprawling analysis, I found a nugget of truth that changed my perspective on my own place in the world, and helped me understand the depth of the connection I felt with my grandmother in a way I’d been missing.

The Fourth Turning suggests that history has a seasonality, that over the course of roughly a century, human society experiences a spring, summer, fall, and winter reflective of the typical traits of those seasons. You can imagine this transpiring something like a play in four acts—in the first act, themes and characters are introduced. In the second, the action starts to heat up. In the third act, tensions rise; and in the fourth, the action reaches a climax that brings everything tumbling down and resets the next cycle of history.

Strauss and Howe call this seasonal history cycle a saecula (pronounced say-cue-la). The present cycle began in 1945, after the end of WWII, while the prior began in 1865, at the end of America’s Civil War. At such turning points in history, society calls into question its highest ideals. What do we believe? What do we stand for? What do we stand against? Each of us is forced into the uncomfortable position of choosing between conforming to a system that clearly isn’t serving us or finding an effective way to defy it.

What part will you play in the story?

The world changed significantly between when I entered high school in 2000 and when I graduated college in 2008. So much of what I’d taken for granted about the present and the future disappeared virtually overnight. My generation had been trained to follow a winning formula: work hard in school, go to the best college, get a high-paying job, and never worry about money again. Raised from an early age to covet our neighbor’s luxury possessions and yearn for little more than a job with a fat paycheck, to wish for something more meaningful was useless folly. Over the course of my adulthood, I’ve tried to let go of the idea that the value of my existence stems from my earning power as an employee or business owner. But to release myself from this fickle no man’s land, I’ve found myself seeking an alternative anchor for the purpose of my existence.

The second important part of Strauss and Howe’s analysis addresses the people involved in making history happen. Like the actors in a play, Strauss and Howe assess that each generation develops a personality that prescribes its role in the constellation of history. Those born in the First Turning they call “Prophets,” those who dream big dreams they’ll never realize (the Boomers of the present saecula), with Artists and Nomads the generations born before and after them, respectively. Those born in the Third Turning, they call “Heroes,” those who come of age responsible for managing the crisis of the Fourth Turning.

Born 75 years apart, in the constellation of history, Marjorie and I were both Heroes within our respective saecula. The shift from the Third to the Fourth Turning brings an abrupt shift from maximal individualism to a rising awareness of the importance of community. The Hero generation is responsible for managing this shift, and founding the institutions that will create a new order that advances a new set of cultural ideals. Born into the Third Turning—she in 1911, and me in 1986–we both graduated college and came of age as adults as our respective Fourth Turnings began.

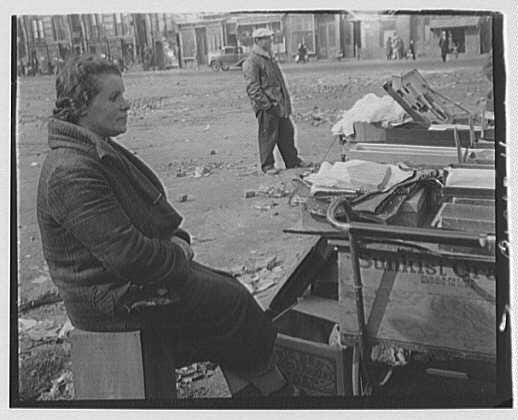

When the financial hysteria of the Roaring ’20s finally crashed in 1929, Marjorie likely felt as unprepared to handle the changed world of the 1930s as I did the post-crash world of the late 2000s. How do you make sense of yourself when the world as you have known it ceases to exist? As humans of the modern age, we are obsessed with logic models, the misplaced idea that we can predict the future against the chaos of nature and lived experience. But when the logic model breaks down, trust goes with it. If I can’t trust “the system,” how can I trust myself – or anyone else?

In the earliest years of her adult life, Marjorie willingly faced these questions and their answers with a quiet, fierce determination I admired. She hadn’t been raised to live in a world of social chaos, but she did so with grit and conviction, somehow managing to forge a truly remarkable life out of challenging unforeseen circumstances.

How will your choices change your life?

Sometimes the future is out of your control. And sometimes, it’s what you make of it.

It took me a long time to realize it’s not just Marjorie’s story I’m yearning to tell, but my own, how her choices both inspired and guided the decisions that have made me the person I am now, and the one I hope I’m becoming. A great deal of life is determined by happenstance and luck – but what you do in the moment matters, too. Even when the options are all bad, the least bad choice is still a decision. Agency always counts for something.

Truth and trust are interconnected. If I don’t know what is true, how can I know what to trust? The absence of trust and truth begets fear – what the hell is happening? And what the hell do I do about it? The modern cult of personal responsibility dictates that fear is a personal problem. If I am afraid, it’s because I’m “doing something wrong.” To comply with the social expectation that each of us is managing the problem, we support a pervasive culture of “This is Fine,” when in fact, our world is on fire.

Life on Earth is inherently tenuous – as humans, nature has never ceased to bring us into dialogue with that truth. There may be seasons of wealth, ease, and plenty, but winter is always coming. It takes a different kind of mindset to survive the winter of the Fourth Turning. It forces us to contend with what is “essential,” and what is not.

When Marjorie chose to marry Gordon and become a spy in 1933, she did so against a backdrop of social catastrophe. Entering college in 1928, she may have imagined an easy, bright future stretching out in front of her. But now the future of the world was at best uncertain, and at worst, grim, with the mismanagement of capitalism at least partly to blame. Working to advance Communism was both her best available career option, and an opportunity to support a nascent, hopeful alternative to a seemingly failing system. “Sometimes you have to just pull up your socks and get on with it,” Marjorie liked to say, her bias for action always evident. By becoming a spy, she was both successfully doing something with limited available options, and taking a stand against the pressures of extractive capitalism.

Marjorie taught me so many things in the years that I had the good fortune to know her. How to iron a man’s dress shirt and how to sew a braided rug. How to cook a perfect porkchop and turn the drippings into gravy. An avid puzzler, I learned to love crosswords by dictating clues to her and filling in her responses after she lost her sight from macular degeneration. She taught me to ask hard questions and give good answers, and that fools are rarely worth suffering.

But perhaps the most important lesson I learned from Marjorie is that a good life is not one made from a steady job and a solid paycheck, though of course resources do help to buffer the strong winds of the winter storm. Sometimes both the fun and hard part of life is figuring shit out when the going gets tough. What have I learned from lived experience? And what choices do I make when shit gets dark, or weird? A well-lived life is a tapestry woven from an array of experiences and emotions, and both my life and Marjorie’s were shaped by extremes of trust and fear, love and negligence, loyalty and betrayal. The tumultuousness of my life trained me from an early age to love chaos above all else, and to relish the puzzle of figuring shit out when the path forward isn’t obvious. (‘It’s only fun when you’re not sure it’s going to work,’ I like to say).

There’s a link between Soviet success propagating Communism and the Trump movement of today. Sometimes “not working” isn’t a puzzle to be solved but an obsolete idea that leaves people hungry for an alternative. The question is, what?

My hope in chronicling the story of Marjorie’s life (and my own) is to get closer to understanding the world we are creating together. To pull apart the social expectations of past generations that have been handed to us and begin to weave them together into something new.

I want to fully recount and remember my own family history – the good, the bad, and the ugly – while also believing it’s possible to write a new story – for myself, for my family, and for the concentric circles of community that create a container for our mutual thriving. To make the future different from the past, we have to imagine how it could be, together.

Will you join me on the journey?

If this is your discovery point for Fetch Me Home, consider starting here:

The Story Starts Here

In my grandmother’s final hours, I sat by her bedside and held her hand. At 17, I was young to be managing the care of a dying woman, but circumstances had made it so. Work obligations had called my mother out of state and my grandmother’s rapid and unanticipated decline left me “in charge.” But in many ways, it was a gift to everyone. My grandmother an…

I’m gaining some hope from the idea that Marjorie kept moving despite the narrowing of her forward path. We need these stories now. This is how we’ll sustain through the fast brewing storm.