The Exorbitant Cost of Everything

How did a "middle class" lifestyle become so unaffordable?

Last Tuesday, I was rushing through Grand Central Terminal on my way home from work when I decided to pop into a bakery for a pastry. The wall was still lined with pain au chocolat, and with ten extra minutes to spare, I figured it would make a perfect snack.

“How much?” I asked, card in hand.

“Seven fifty,” the cashier said.

I stared at him for a long fifteen seconds.

“Seven dollars and fifty cents? Are you serious?” I asked, incredulous.

“Yeah,” he said, apologetic. “Our prices just went up yesterday. People are pretty upset.”

I thought about the mornings I had seen people line up here for their daily pick-me-up. I had no idea what these used to cost, but any price hike that put them over seven dollars would surely make an impact.

I recalled my trip to northern Spain last summer, marveling at the €1.20 loaves of bread. (Would any European ever tolerate €6.90 for a simple pastry?) And yet, in New York, this was becoming the norm.

I bought a bag of chips for $3.00 and walked out.

The phrase “affordability crisis” is thrown around so much it feels detached from reality. It’s like hearing zoologists describe the mating behavior of primates… when you’re the primate.

I’ve written variously about what it’s like to not have enough money to live. Three months ago, I started a new job, expecting it to change my financial reality. But it hasn’t—at least not as much as I hoped. I am not poor as I was a year and a half ago. But but I am or not, I feel ALICE: Asset Limited, Income Constrained, Employed.

Our family of four (economically speaking, I’m counting my two stepdaughters as one child since they split time between two households) faces the hard truth that the best-case scenario for two college-educated parents is just barely making ends meet.

For 17 of the past 24 months, my life felt like one long existential crisis. My father-in-law was dying, I was unemployed, and expenses kept piling up. As Andy and I formalized our vows, we clung to the hope that relief would come soon. It finally came—in good and sad ways: I got a job, and my father-in-law passed away.

But now, here we are in a new “normal” status working. Working 40 hours a week, commuting nine hours across two days, and ending up with just $200 a week in disposable income doesn’t feel like stability. If anything, it’s more stressful than the temporary burden of unemployment or end-of-life care. This isn’t a temporary hardship. It’s just… life.

Here’s a breakdown of our monthly expenses:

With a monthly net income of $9,500, we have about $850 left for everything else. That’s $200 a week to cover dining out, date nights, extra babysitting, clothing, household items, and price fluctuations (like eggs). It also has to cover subscriptions, entertainment, and kids' weekend and after school activities. Any expenses beyond this get charged and paid later.

Thanks to my employment, this isn’t the complete picture. First, I have a health spending account that covers medical costs, and health insurance that offers decent coverage after that is wiped out. Second, I pre-pay $5,000 in childcare expenses, which would average out to roughly $400 a month, but really winds up being $1,000, five times a year. Lastly, two five-week months of the year, I get a third paycheck (by nature of “bi-weekly” being 26 times a year). Our margins are too thin to allocate this monthly, but it’s $7,000 that we can save to spend on summer camp or travel or Christmas presents. (More often than not, it’ll windsup offsetting the margins of debt that accrue over the $850 monthly flex allowance)

Interest payments account for nearly half of my take-home income, thanks to interest rates between 8.5% and 22%. (More than $2,500 of our monthly mortgage payment is just interest.) We made some large financial decisions in the past two years—a mix of necessary home repairs, a wedding, and a rare family vacation—which we’re forced to contend with on a monthly basis. It’s the cost of trying to maintain a middle-class existence in America.

And we’re clearly not alone. Americans’ total credit card balance is $1.211 trillion as of the fourth quarter of 2024, according to the latest consumer debt data from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, up from $1.166 trillion in Q3 2024 and is the highest balance since the New York Fed began tracking in 1999, an average of $6,730 per person. Between Q3 and Q4 of last year, credit card balances rose by $45 billion.

FORTY FIVE BILLION DOLLARS, y’all.

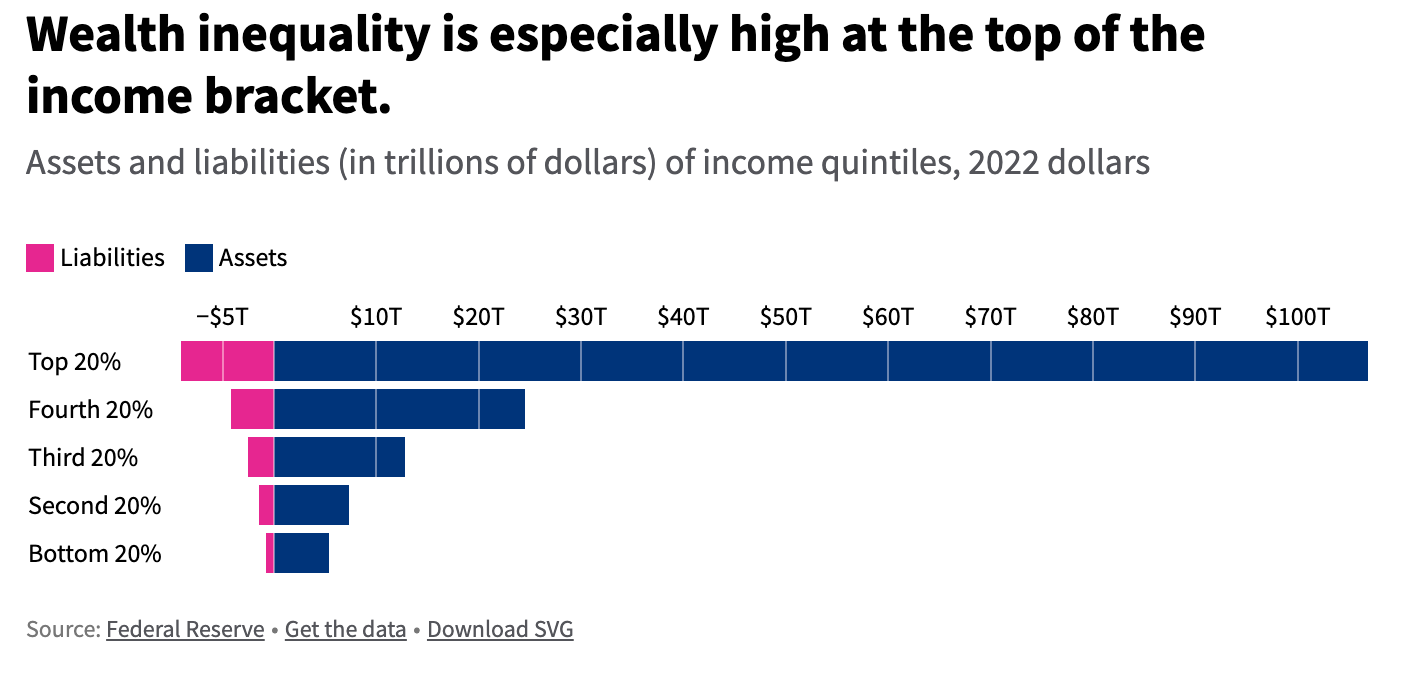

Even households in the fourth quintile feel the financial strain. A graph from USAFacts illustrates how income inequality affects wealth distribution:

USA Facts: How Income Inequality Shapes Americans' Wealth

The Fourth 20% have less than a quarter of the assets of the Top 20% but almost half the liabilities. In essence, we are financing our way to a comfortable life, paying the cost of debt just to get close to what the top 10% experiences effortlessly. (I’d expect that the asset-liability balance may be the worst for the bottom 5% of the Top 20%.)

Whether that fourth quintile is ALICE depends a great deal on where you live, but the geographic location of a good paying job is more often than not close to where the cost of living is the highest. (While the cost of a house in Missouri might be lower than Connecticut, the primary downside of the middle of the country is it doesn’t offer access to a New York City paycheck.)

And it’s not getting any better. On a recent episode of The Ezra Klein Show, economist Kimberly Clausing explained that Trump-era tariffs will disproportionately affect low- and middle-income Americans because we are the ones most vulnerable to price increases.

Ezra Klein Podcast: Kimberly Clausing on Tariffs and Inflation

As you can see in the graph above, it’s the top 20% who have the income to support savings. The other 80% have to find ways to make ends meet.

There is no singular solution to this “crisis.” For families like ours, there is no room for financial missteps. The cost of living has escalated to the point where even those with decent incomes are living paycheck to paycheck, accumulating debt just to stay afloat.

I don’t know the way forward, but I do know this: If a pain au chocolat costs $7.50, we’re past the point of crisis. We’re in survival mode.

I felt weird "liking" this, but the reality is you put into words so clearly what the vast majority of people feel. As someone who literally left the US in part because of the cost of things, I don't understand how people are doing it, nevermind with children. I commend you for your transparency and activism around this!