The journey from childhood to adulthood is shaped by both intent and happenstance. The unique combination of a person’s qualities and curiosities, along with their parental influences and incidental circumstances, influence the singular direction of a person’s life.

A Bright Future

My grandmother Marjorie Tilley was born in New York on September 8, 1911 to Bertha Anderegg, a French Swiss national, and John Lewellan Tilley, an Englishman. Bertha and John had wed two years prior, on June 5, 1909, but in Marjorie’s early years, their relationship ended, and her father disappeared.

Her mother, a housekeeper, ran a boarding house at 122 East 30th Street on Manhattan’s East Side. One of Bertha’s long-time residents, Albert Bard – an attorney and confirmed bachelor – became a grandfatherly figure to Marjorie, encouraging her intellectual curiosity and ambition.

Marjorie was a curious and precocious child, always seeking opportunities to read and learn. In her early years, she attended the local public school in New York, but as she grew older and her intellectual promise became more apparent, Bard likely encouraged Bertha to send Marjorie to school elsewhere.

As an immigrant relegated to drudgery, Bertha wanted more for her daughter than she had the chance to achieve herself. Instead of obligating her to house chores, she required Marjorie to study, expecting dedication and academic performance from her daughter as the reward for her own personal sacrifice. Her only child, Bertha raised Marjorie with love, care, and a clear expectation that she would use her keen intellect, and the opportunities provided to her, to make something of her life.

In 1925 at age 13, Marjorie enrolled in Roosevelt High School in Yonkers, NY, during which time her mother continued to live and work in Manhattan, sending her daughter to board with a family. Marjorie excelled at Roosevelt, serving the Skull and Key honor society; the school yearbook, Envoi; the school newspaper, The Crimson; the sketch (drawing) club and Triphi, the school social club as an enthusiastic leader. She graduated at 16 at the top of her class.

Marjorie (nicknames “Tillie” and “Marge”) is remembered this way in her high school yearbook:

“She casts bright looks at everything.”

“Tillie’s most outstanding trait is her perpetual cheerfulness. Nothing seems to disconcert her, ever. Even four years of Latin have not lowered her standard or her optimism. She attacks whatever work there may be with responsibility and individuality. Those who have worked with Tillie on the Crimson Echo (the school paper) know her “nose for news.” For Triphi too, she guards the bulletin board zealously, even if she can not quite reach the sign herself. Were it not for a keen sense of humor, which jumps out at certain inopportune moments, and a weakness for cream puffs and pickles, Tilley would be astonishingly sensible.”

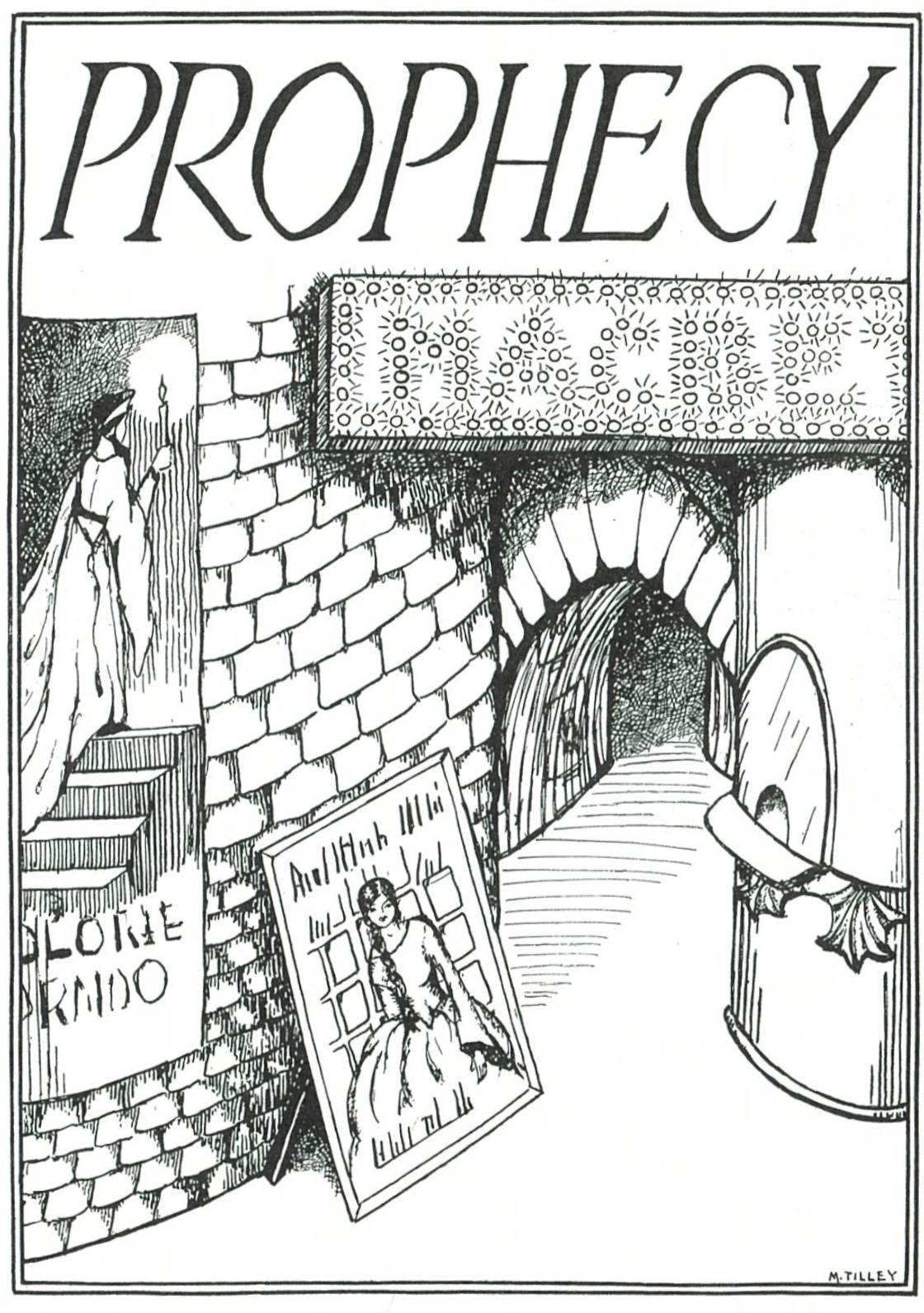

As a yearbook editor, Marjorie wrote and illustrated 'Class Prophecy', a section imagining what each member of the class would be doing 20 years in the future. The Forecast for 1948 is composed of excerpts from letters sent by a fictional classmate who visits with every member of the class as she travels around the world in a touring production of MacBeth.

In her missive from Paris, France sent on May 29, 1948, the correspondent reports seeing Marjorie, “a dress designer,” along with a handful of other classmates living in that fashionable city. It’s hard to know if becoming a dress designer was Marjorie’s primary ambition, or simply one of many possible avenues she imagined for herself. Either way, this is a glimpse into her vision of a glamorous and worldly future abroad.

As Valedictorian, Marjorie had the privilege of giving her class address. The local paper, The Yonkers Herald, reported on her speech with enthusiasm:

“Miss Marjorie Tilley’s fine essay, which she delivered with an assurance and felicity which added greatly to its content, was entitled “The Magic Carpet of the Mind.”

‘Legend tells us,” said Miss Tilley, “that in ancient days a prince owned a magic carpet on which he had but to step and be instantly carried to any place he wished. In this prosaic age, we have no such obvious magic, but we may journey on the magic carpet of the mind. Words, by their amazing combinations, become luminous, and we are transported to magic lands. Childhood’s magic is the most wonderful of all, and the Immortal Alice creates a series of beautiful pictures in the mind.

‘As childhood slips away, the only escape from the drab realities is on the magic carpet of the mind. The inventor first sees his ideals, the sculptor the image of the statue, the statesman and diplomat envision an era of universal peace and brotherhood, the author lives with his brain children, the engineer sees each bolt and rivet. After our active life is over, the carpet still is potent as ever, and we can go back to well-loved places and friends of long ago.

As we tonight look into the future and see our tasks, the magic carpet awaits us with rest, brief glimpses into the world not of reality, [but of] high adventure, and escape from the prosaic reality of every day.’”

I can see Marjorie – all of five feet tall – peering out from behind the lectern, full of pride at her achievement and full of hope for her bright future. Marjorie had let the Magic Carpet of the Mind inspire her own imagination of what her future might hold. With a keen mind for dates and details, and a love of art, she bounded from high school into college full of enthusiasm and hope. As class Valedictorian, Marjorie was awarded a full-ride college scholarship to Vassar of $650 a year.

A Dream, Realized

In her first two years at Vassar, Marjorie suddenly found herself a small fish in a much bigger pond, moving from a class of 68 graduating seniors to a first-year class of more than 300 young women. Having spent the last three years living away from her mother, she was already accustomed to the routine of living on her own. Stepping into the collegiate world of academic rigor and wealth may have been more difficult. Though she continued to exert herself academically, her results were less commendable, earning her Bs in her introductory-level courses. In her first two years, her areas of study varied widely as she surveyed the possible areas of academic focus in which she might want to major. Her first-year courses included English Composition, French Conversation, Animal Biology and Medieval and Modern European History, as well as “the Oral Interpretation of Literature” and “Principles and Hygiene of Physical Education, “a course designed to help students to direct their activities in accordance with modern health standards” which included the “study of health habits, mental hygiene, and nutrition,” presumably an early indoctrination into diet culture. In spite of the gains of the first wave of women’s liberation, there was no escaping that college was also a finishing school, meant to teach you how to guard your figure. It was also during this time that, induced by her peers, Marjorie began smoking a pack of cigarettes a day, a habit she would carry with her into her 70s.

Marjorie’s academic interests began to take shape her sophomore year. She enrolled in Critical Writing, Shakespeare, Introduction to Modern Government, and French Literature, in addition to an education course on “The Advancement of Learning,” which explored how education had changed over the last 50 years. A philosophy course, “Introduction to Ethical Problems,” an introductory survey of the moral problems connected with the home, art, industry, politics, religion, and international affairs,” would have invited Marjorie to interrogate ideas she may have previously taken for granted. This was the year that Marjorie found her major: History. With a keen mind for details and an encyclopedic memory of people, places and dates, I have to imagine she felt awed and excited by how much there was to learn about the wider world.

She enrolled in two history courses that year. The first, “The Far East,” explored “the Orient in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries with an emphasis on modern India, the growth of Japan into a world power, the awakening of China, and the commercial interests of the East.” The second, “Modern Russia,” examined the “political, social, and economic conditions in Russia during the modern period and the general relations of Russia to Western Europe and Asia. Stress is laid upon the Revolutions of 1905 and 1917 and the Soviet regime.”

Both courses were taught by Lucy Textor, an unmarried and accomplished academic who likely had an outsized impact on Marjorie’s imagination of her professional future. Professor Textor began teaching at Vassar in 1905, and continued to do so for more than 35 years. She traveled widely to conduct research on the countries of Eastern Europe and Russia and would have reported a great deal of observational detail in her courses. The following year, Marjorie enrolled in Professor Textor’s course on the contemporary history of Central and Southeastern Europe, “a study of the recent history of Poland, Austria, Hungary, Czecho-Slovakia, Rumania, and the peoples and states of the Balkan Peninsula.” In 1929, Textor would share in a public forum that she thought the Soviet government to be “a great experiment,” one she would not judge until it had the chance to prove its worth. Was Lucy Textor a Communist? It’s impossible to know, but it’s possible and even likely that this in-depth exposure to emerging Communist ideals made Marjorie more receptive to the cause.

Waking Up to Reality

In 1931, three changes would shift the course of Marjorie’s life: the economic fallout of the Great Depression, Gordon’s return from time abroad, and her own evolving attitudes about the value of education.

Economic conditions declined rapidly as public alarm about the recession becoming a depression intensified. That year, more than 2,300 banks failed, vaporizing $1.7 billion in deposits overnight. These bank failures led to more than 20,000 business failures, and unemployment rose from nine to 16 percent. In 1932, another 1,700 banks failed and unemployment rose to 23 percent.

It is difficult to imagine nearly a quarter of workers losing their jobs, suddenly unable to make a living. These circumstances surely changed Marjorie’s calculus about her likely future. Marjorie may have lost hope that her earlier life ambitions would be easily realized. The euphoric hysteria of the 1920s was over. The stark reality of the Great Depression had arrived.

Towards the end of 1930, Gordon returned to New York City after an extended period living abroad. The two first met seven years earlier when Gordon visited Albert Bard at Bertha’s boarding house – Gordon was 19 and Marjorie was 12. By 1931, the sheepish 12-year-old schoolgirl had blossomed into a confident young woman. It’s hard to know if it was Albert Bard’s influence or Marjorie’s attractive qualities that piqued his interest, but the following February, Gordon began courting Marjorie in earnest, visiting her at Vassar and persuading her to make regular trips to New York. The meet-cute of their first romantic encounter is lost to history, but it is here, dear reader, that the glimmer of my own future first comes to light.

Life at Vassar was also changing, as was Marjorie’s academic performance. Likely submitting to public pressure to allow for the progressive demands of women’s liberation, Vassar adjusted its policies to extend dorm curfew to 10pm and allow students to socialize with male visitors without parental approval, making it easier for Gordon and Marjorie to spend time together without intervention or oversight.

In her Junior year, Marjorie’s grades show the compound influence of the distraction created by Gordon’s courtship and a lax attitude towards her studies. Steady “Bs” in her first two years quickly dropped to Cs across the board (with the exception of her courses in Art where she earned As). Gordon tried to persuade Marjorie that she was wasting her time getting a college education, but she remained stalwart – still motivated by Bertha’s sacrifice, she felt she owed it to her mother to complete her degree.

Marjorie had always loved learning, optimistically believing that if she dreamed big and worked hard, her ambitions were within reach. In the past, striving to be the best had always delivered the desired result. Now, as graduation neared, it seemed evident that being the best wouldn’t have the payoff she might have once imagined. In a world of economic turbulence, a college degree might not guarantee the future promise it once had. Whereas she may once have imagined a path from her studies to a glamorous future as a dress designer in Paris, now the path to an alluring future was uncertain, and the effort required to get good grades hardly seemed worth it.

In the summer of 1931, Marjorie and Gordon both attended a bi-weekly lecture course at the Workers’ School in Manhattan, where Marjorie reports them becoming “mutually interested in the spirit of Communism, Marxian Dialectics and the way they were being worked out in the Russian Experiment.”

In the fall of 1931 – her final year at Vassar, Marjorie enrolled in an advanced American literature course which addressed “the moving frontier and the changing conceptions of democracy and of art,” while at the same time studying the writings of Voltaire and Rousseau, leaders of the French revolutionary period, in the original french. At the same time, she took two history courses, a History of Western Europe, which included, “study of the recent history of France and Italy, with emphasis on the problems of nationalism, imperialism, and internationalism,” and a course on the United States since 1850, which explored “the Civil war, reconstruction, aspects of national development since 1880, the United States as a world power, and the part of the United States in the world war.”

So closely following her courses on Modern Russia and Central and Eastern Europe, alongside the economic collapse taking place around her, her studies may have left Marjorie with deeply held skepticism about the United States as a world power and the strengths (or weaknesses) of its prevailing ideology: capitalism.

Here is a woman who has spent the last year immersed in the history of Russia and Central Europe now examining the implications of imperialism and war while at the same time contemplating the original texts of the French Revolution trying to make a decision about the future direction of her life. As the social and economic structures around her falter at the tipping point of incredible profound change, how does she integrate a growing public sense of despair with her own worldly desires?

Here, Gordon comes to her rescue with an offer that she can’t beat and as such, she can’t refuse: marry him and travel with him to Europe in support of the Marxian ideals of the Soviet experiment. Even as the world around her grew increasingly chaotic, Marjorie was never one to let circumstances beyond her control dampen her own resolve. She had envisioned a life abroad, even at the tender age of 16. Standing on the edge of adulthood, preparing to face graduation and an uncertain future ahead, I have to imagine Marjorie felt somewhat disappointed but also a little proud of the opportunity she had created for herself. Having gained the favor of a handsome, eligible suitor, she had secured the most prized achievement of womanhood: a future husband. Bonus that he came with Marxist ideals and worldly ambitions. Amidst the dreary desperation of the Great Depression, Marjorie was pragmatic and resolute, ready as ever to pull up her socks and seize the moment.

Having faced a similar circumstance on my own eve of graduation, I like to imagine that Marjorie was confident and clear-eyed in her conviction about her decision. But she couldn’t have foreseen how this one simple choice would change her life forever.

If this is your first time reading Fetch Me Home, consider going back to the beginning, here:

The Story Starts Here

In my grandmother’s final hours, I sat by her bedside and held her hand. At 17, I was young to be managing the care of a dying woman, but circumstances had made it so. Work obligations had called my mother out of state and my grandmother’s rapid and unanticipated decline left me “in charge.” But in many ways, it was a gift to everyone. My grandmother an…