It’s the 8-year anniversary of the day after “The Morning After” Donald Trump was elected the first time. Maybe it’s finally time to stop “fighting” and start thinking in a different direction.

There are so many people who feel gutted about Tuesday’s election result.

I don’t fault Harris for this loss. She took the wheel of a moving vehicle and drove like hell as hard as she could in what seemed like the right direction. She inherited a host of Presidential and Democratic Party strategic choices she had no part in. She ran the playbook she was handed. And it didn’t work.

While it’s easy to pin this on the candidate, the sitting President, and their party’s lack of strategy, there’s something bigger, something deeper going on here.

Can you feel it? The truth in this election result? The roiling discontent of so many millions of people cannot be unjustified.

Donald Trump sports a self-made superhero cape and portrays an alternate reality that enough people want to live in, they are willing to make him President.

I think it might be helpful for those disappointed by this result to think about this like a technology problem.

Typically 13.5% of any group, Early Adopters embrace new technology and are exhilarated by the promise of new and better. We don’t love to deeply investigate the long-range implications of our decisions, but we love choices that make us feel like life is getting easier, more efficient, more streamlined.

On the other side of the curve lie the Laggards, who we might critically call “Luddites,” the 16% of the population who would rather balance a checkbook than bank online. In between, the other two-thirds of the population evenly divide between the Early and Late Majorities, those who after some cajoling, will come around to an idea. (Just 2.5% are “Innovators,” those who actually generate novel ideas that move through the population).

It seems to me that the technology of eighteenth-century American democracy is broken. It’s a clock that may look grand, but no longer effectively tells time. Of course, the Laggards would sooner kill other people than part with their ain’t-broke-don’t-fix-it Constitution. But the truth is, American political technology was specifically created to advance and support free-market capitalism, a dominant—and nostalgic—notion of economic freedom, one that fails to deliver for the vast majority of people. In the 21st century, America needs a new kind of political software, one that can serve the needs of our increasingly diverse country and provide a bedrock for a sustainable economic future.

The technology of democracy is broken in two ways. First, it never worked that well to begin with, and people of various persuasions have worked hard for centuries to try to apply patches to the code to improve it. It’s not designed for inclusivity. It’s designed for top-down control by an elite few, political levers both parties have exploited for decades.

Now this old and antiquated technology is doubly broken because it’s been overtaken by an ideological virus, whose goal is simple—to enrich itself at all costs. Like any virus, it will rewire the system’s code and destroy anything that doesn’t serve its ends, using flashpoint issues and identity factions to pit people against each other to serve its ends. The virus will burn it all down if it helps its cause.

There is a strange opportunity in this devastation. It seems to me that the opportunity no longer lies in repairing and improving the old system, but instead presents an opportunity to build something new.

Change we can believe in?

When Donald Trump first won in 2016, after I had spent nearly 1000 hours trying to swing Florida for Hillary Clinton, I thought that the Democratic Party would realize the error of its ways, that it would begin casting around for ways to fundamentally change the political process. Instead, the candidate “took responsibility” for her mistakes, and the Party tried to do a better job playing the Republican’s political game. In 2020, Joe Biden got lucky by slim margins in key places, and managed to slide back into the White House. But he and his team internalized that as a validation of strategy rather than a fluke. The 2024 election is an unequivocal endorsement of the burn-it-down hellraiser. If you didn’t hear it loudly enough the last two times, the people want a change.

This desire for change isn’t new. And there are those, like

, who argue that if Democrats could simply build a coherent communications ecosystem that could compete with the propaganda system of the right, they could convince average Americans to support a Democratic candidate. Actually holding a lowercase democratic primary could help! But these are still Band-Aids on a deeper ailment we’ll likely have to address before the nature of politics in America really improves.Some helpful nostalgia…

In 2008, Barack Obama successfully ran for “Change We Can Believe In” and his plan to “renew America’s promise,” which voters from nearly everywhere rewarded with a resounding majority victory. People thought that Obama was finally going to reverse the terrible economic consequences of NAFTA, that had devastated America’s middle class over the previous 15 years. But when Obama showed himself to be a slightly-more-progressive-than-Bill-Clinton neo-liberal technocrat, people were confused. This wasn’t the change anyone asked for, just more of the same.

After Hillary Clinton commandeered an anointing rather than hold an open primary in 2016, she ran Obama’s 2012 General Election strategy, thinking an unpopular white lady could be elected with the same strategy that elected a popular Black man. In so doing, she demonstrated how fundamentally out of touch she and the Democratic Party establishment were—and continue to be—with the lived reality of a majority of Americans.

What reality, you ask?

Check out this graph of the change in real income over a 40-year period, from 1979 to 2019:

Your might be tempted to discount the 1% as the “millionaires and billionaires” but you’re wrong.

Top 1% of Earners $819,324

Top 5% of Earners $335,891

Top 10% of Earners $167,639

Household income over $167,000 puts you in the top 10% of wage earners in America.

And its actually worse than that:

Between Q1 1990 and Q2 2024, the wealth held by the top 1% grew from 16.5% to 23.3%, while the wealth held by the top 2% to 20% rose from 43.7% to 47.4%. At the same time, the percentage held by every other group either fell or remained flat. Source.

If you’re among those whose real earnings or net wealth have increased over the last 20 years, you’re among the privileged minority of Americans who have benefitted from widening economic inequality. Those who’ve been left out by that widening inequality gap, largely due to the offshoring of American industry thanks to NAFTA, are PISSED!

They were promised an American Dream for themselves and their children that has turned out to be an American NIGHTMARE!

Now, let me be perfectly clear: The virus in the system of American democracy doesn’t care a whit about these people and their plight. It’s simply figured out how to harness their discontent for its own political gain.

And our antivirus software—the two-party system—seems incapable of stopping it.

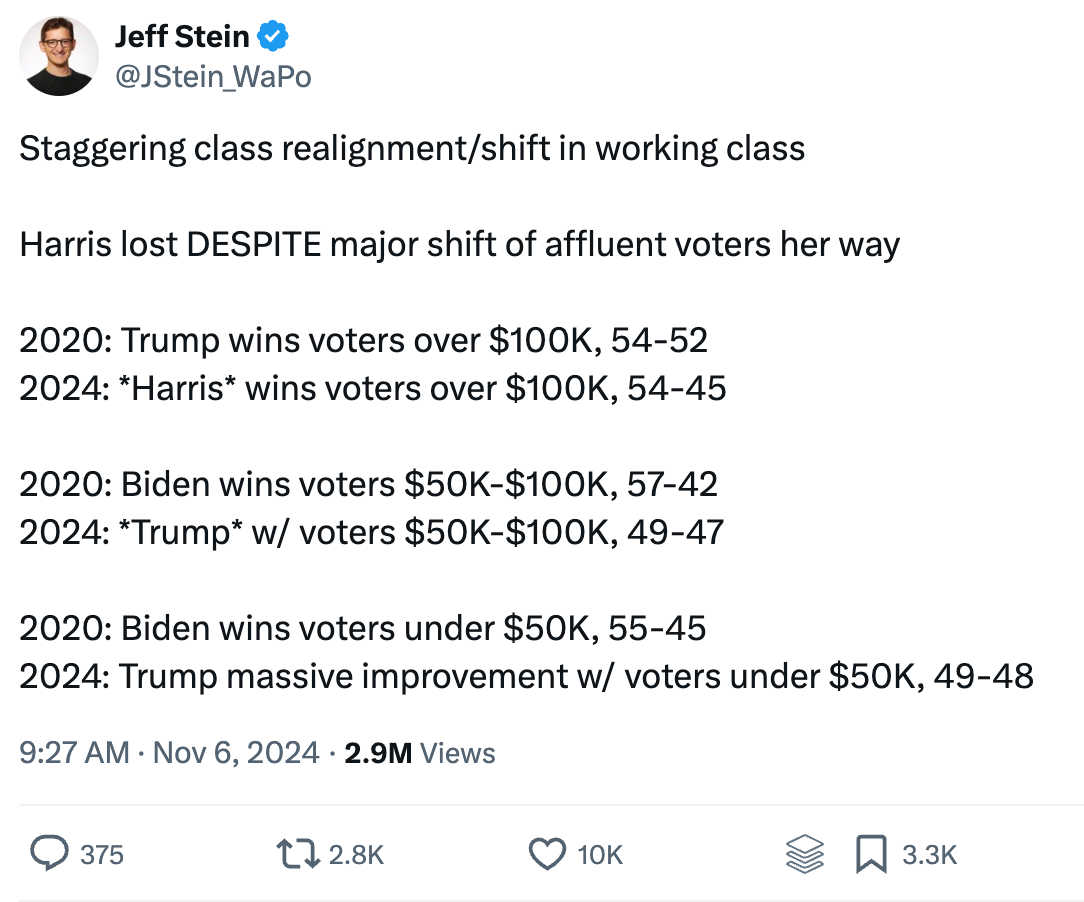

The truth is, Democrats aren’t just out of touch with reality, they don’t appear to care, answering complaints about America’s affordability crisis with insistence on improvements in macroeconomic indicators. In the same period of time, Democrats have become the party of white, college-educated people, those who like to think of themselves as “middle class” because that’s how they were raised, but who are in fact the vanguard of America’s burgeoning upper class. They have held up “free college” as the solution to a much deeper, more complex problem in the American economy, and people aren’t buying it.

American workers have seen technology transform the landscape of work and free trade decimate industry and opportunity over the last two decades. At the same time, the increasingly visible Republican political machine has made hay in the sunshine of Democrat’s epic NAFTA failure, building the propaganda machine that is Fox News alongside robust state and county-level party organizations. Meanwhile, the state-level Democratic Party infrastructure has aged and stultified, frantically activating during the three months of a presidential election, and otherwise going underground.

The System is Broken—But what does that mean anyway? (2017)

The Democratic Party establishment has run out of steam and out of runway. There’s no gas in the tank and no roadmap of where this vehicle is headed. It’s lost in the wilderness, frantically trying to pretend it knows where it’s going. (NYT: Nancy Pelosi Insists the Election Was Not a Rebuke of the Democrats). (Admitting you’re lost is typically an essential first step to actually finding your way.)

To fight back, or to surrender?

In response to Trump’s victory, many people are doubling down on our need to “fight harder.” I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again: “fighting” fire with more fire just creates a conflagration liable to make losers of us all. Any fight requires energy, and there simply is no sustaining energy for a fight against a virus that has converted the system to its will.

Fighting is also a losing uphill battle as the organizers who worked tirelessly on Harris’s ground game in WI, MI, and PA over the last three months have surely realized. The virus won by preying on weakness, rooting through people’s worst impulses, sowing resentment and distrust. It took the fear caused by very real economic distress and alchemized it into jingoism and a roiling distrust of immigrants. It’s incredibly hard—maybe impossible—to win that uphill fight.

Progressives naively pressured Harris to make the case for herself with policy, but policy talking points only strike people as inauthentic. A better approach would be to create an alternative approach from that of viral fear, one that might not be so appealing to the baser instincts but which presents a common-sense, localized alternative to the chaos being wrought at the federal level.

What Bucky Fuller said is true:

“You never change things by fighting against the existing reality. To change things, build a new model that makes the existing model obsolete.”

This moment offers an invitation to surrender our belief that our lives actually depend on the federal government at all. Let’s look to our towns, cities, neighborhoods, and states to provide the infrastructure of reinvention and resilience. We need to consider together what we stand for at the level of “community” rather than identity. What is the new political technology we need to build to replace this broken system? What are the shared values that will guide the path forward?

What are your values?

The day after the election, my good friend Dylan shared his commitment to keep on keeping on, guided by his values, which he listed in his email. How many of us have taken the time to define our values? Have you ever been part of a community discussion where you talk to other people about their values? And the values you have in common?

What are you afraid of?

Five years ago I wrote a book. I was still reeling from the grief and disappointment of losing the 2016 election, trying to find ways to convert my life experience into something meaningful and helpful. Though the pandemic hadn’t yet started, I could see how the world was already starting to burn. I believed I had both the ability and responsibility to …

After 2016, I swore these kinds of discussions were the way forward. I experimented with hosting small community workshops with relative success in Brooklyn with the Brooklyn Vision project, and with less success elsewhere. I realized that the conversation is only half the objective. There has to be someone listening who promises to do something with this new insight and understanding. (I spent a lot of 2017 trying to persuade the Democratic Party that this strategy could help lay the groundwork for future victory, but they were too busy trying to figure out how to beat the Republicans at their own game.)

One other key piece of insight I’ve gained since those experiments is that communities are the most robust node of organizing we have. What constitutes a “community” is open for discussion, though it might feel obvious. Sometimes, community is anchored by a municipality. Other times, it’s more of a geographic area. A university can be a community, and so can a large corporation. Still other times, it’s a geographically dispersed group of people who hold a shared set of beliefs.

While the virus-infected federal government can slash funding and withdraw our rights, communities can invest in services, and reinforce solidarity and mutual aid. Values-based organizing at the community level can help counteract and inoculate against top-down federal tyranny. It’s also the smallest viable framework within which to experiment with how we might better understand and address what people really need to feel supported, happy, and healthy. We can write the beta version of the code that might resurrect a high-functioning federal government and finally deliver a technology of democracy for this century.

America’s Constitution, the longest-standing founding document in the world, has been in place nearly 1.5x longer than the runner up, Switzerland, whose constitution is 175 years old (though it was completely revised in 1999). We’ve enshrined a culture that’s aggressively proud of this long period of democratic “leadership,” but from a political technology standpoint, it’s a little like being maniacally proud of still running on MS-DOS. It was certainly groundbreaking in its time. But wouldn’t you trade it for iOS 15 in a heartbeat? There are other ways to run a functioning democracy, as evidenced by virtually every European nation. That’s not to say that any of those models deserve replicating in America. But we shouldn’t take the failure of an aged legacy model as an indication that the premise of government for the people, by the people can’t work. It just doesn’t seem to work like this.

Change starts with us

It’s time to get curious: about your neighbors, and the people you don’t know who inhabit the communities you’re a part of. It's natural to be angry and disappointed when something doesn’t go the way you hoped, and to want to find a way to channel that negative energy into something positive. But we shouldn’t be disappointed or even surprised by the epic failure of antiquated and brittle technology. It’s really a miracle it’s held up this well for this long, (though some would argue its failures have been evident for a lot more than the last 25 years…).

Still, it’s not time to be mad or even distraught. It’s time to start asking people what they care about and what they believe. Yes, you’ll certainly encounter people who believe some complete whack-a-mole things they’ve learned from the propaganda factory. But you have to push past what they think they know to why they want to believe it’s true. What part of their existence or worldview would be damaged by the truth that is reinforced by their chosen alternate reality?

The Brooklyn Vision Project still has durable assets that show what we accomplished in more than a year of engaging with Brooklyn Democrats about their political vision for the future. (And it may have been even more impactful if it had had the party establishment behind it.) It’s also just one example of how to ask people to get engaged in defining a different future together as the first step in designing a more human-centered politics.

Who gets to decide who gets to decide?

I often think about the choice behind the choice, the individual or group who decides how an influential decision will be made.

I’m sure that a primary-tested candidate with a better campaign strategy and a supportive media ecosystem would have given the Democrats a better shot at winning the Presidency in 2024, and would do so in 2028. But we’re playing a losing game against a stacked deck. And the virus in our democracy will almost certainly rewrite the rules in profound ways before the next election comes around, if it even does. But energy directed at the virus only feeds its engine of destruction. We need to forge a new path to solve the problems facing America. We have to think beyond the status quo. The Innovators and Early Adopters have to get started trying something fundamentally new, anchored in a deep belief in something profoundly better.

I'm curious about the fears and hopes of my neighbors—especially those who voted for Trump. I'm curious about those who don’t feel heard, and about why men—yes, even Democrats—take up so much space in our public discourse on politics and economics. I hope new political technology can ensure that future generations of women (and non-men) are granted the voice they deserve in designing our collective future. I know it’s going to be hard, and even terrifying at times. But I will continue to be curious and open-hearted about how we got here, and where we go now.

I hope you’ll join me.