This weekend, I found myself sorting through a collection of paper I’d amassed some decades earlier. Birthday cards from my grandmother, college graduation cards, pay stubs from my ranch job in Colorado, alongside college math tests, early personal narrative essays, a map of California, and a large collection of honorary medals. What had these objects meant to me that I’d made the decision to squirrel them away so many years ago?

I’ve always had an outsized attachment to physical mementos, be they plane tickets, play programs, or other paper artifacts. Holding it in your hand is enough to conjure memory in a way a digital artifact cannot. I mourn the emails I’ve lost to posterity while I cling to the letters I’ve collected over the course of my life.

Yet, tangible mementos are complicated and cumbersome. They require physical storage space not available on iCloud that one may take for granted in a family home.

Leaving a paper trail of where I’ve been seems like the surest way to remember who I am, something that hasn’t been easy in the midst of a turbulent life.

My experience of permanence and place shifted drastically when, at three years old, my home metastasized in two, when my father left my mother.

My mother had always been a tumbleweed, and my father’s departure unmoored her fledgling roots.

From the time I was four until I went to boarding school at 14, we moved eight times. Almost every year, we loaded our belongings into boxes slung into the back of a moving truck or my mother’s Jeep, and found new places for everything. Those objects that didn’t have a place found their way into a storage facility that my mother maintains, to this day, more than two decades later.

Between my parents, I had lived in 15 homes by the time I turned 14, when I went away to boarding school, and then college. While school offered its own kind of geographic permanence, I still had to move rooms every year, packing my possessions into boxes to store, or finding on campus jobs that afforded me summer housing in yet another dorm room. I spent one summer in Spain as an au pair and another in Dominican Republic. The dorm rooms and the summers abroad would add another eleven places I’d lived for anywhere from two to ten months.

Between age 22 and 36, I held leases or living agreements in 10 different places, including Paris, Baltimore, northern Virginia, Washington DC, Brooklyn, Munich, and western Connecticut. I learned to overlook the benefits of deep roots and favor the adaptability of transience, to value the momentum of an object in motion more highly than the stasis of staying put. For much of this time, I made my home in big cities where transience was normal, which meant being a tumbleweed generated its own kind of belonging.

And yet, in the decades I (s)tumbled aimlessly from place to place, I still enjoyed the anchor of a home.

When I was 18, my father and stepmother bought a house, razed it to the ground, and built their own in Boca Raton, FL. Only three times in more than 20 years did I actually “live” in Boca, but each was an important crossroads. The first time, I was 21, trying to find an internship after being rejected by the US State department; then again for two months in 2008, after graduating from college, unsure what exactly to do next; and then for three months in 2016, when I temporarily moved to Florida to work on the Clinton campaign.

As I made my way to more than 40 countries around the world, I felt my sense of self expand with each new place I visited or lived, each new language I learned. Each place added a stone to the stack of memories that would shape the person I would become.

In the intervening time, my father and stepmother divorced, which introduced some emotional changes, but the house remained.

Having a home you live in day to day is both practically and emotionally stabilizing. As a species, we are constantly wrestling with what “belongs” to us, and home offers a convenient place (rightly or wrongly) to situate our domain of ownership. It’s a convenient place to keep food and clothes, books and toys, documents and photographs. But it is also a place that accumulates memories, moments in time that place tiny tenterhooks into your heart, anchoring your emotional self to that physical place. The longer your emotional self rests in a place, the more firmly anchored you become to it.

My father’s house in Boca was both a great place to park a box of adolescent artifacts and a fine place to celebrate Thanksgiving and getaway from the northeast cold in winter. It also incidentally became a fallout shelter for my life’s most uncertain moments.

Finally, after 20 years, for reasons that are bittersweet, my father has finally decided to sell the Boca house he and his ex-wife built together two decades ago.

This week, I returned to do my part to address the artifacts I’d accumulated there. I was sure that somewhere in my closet lay a bankers box of papers and trinkets, but I discovered that at some point, it had gone missing.

This led me on a wild goose chase, diligently opening each of the bankers boxes that had sprouted up in various closets and corners over the years.

One I stumbled across contained a brown file folder that contained two manila folders in it, one for each of my fathers’ parents with their name and a label in my grandmother’s handwriting: NEVER DESTROY.

What, I wondered, had been sufficiently important to my grandmother that she’d instructed that these documents should survive her death?

Overcome with curiosity, I opened the folders, carefully paging through each piece of paper. In it was my grandfather’s death certificate and the bill for his funeral almost 40 years ago. In addition to his graduation bulletin from Brooklyn Polytechnic, my grandfather had kept various letters my dad had sent him over the years; one—an unsolicited appreciation note, included mention of my parents’ plans to maybe have a child—me.

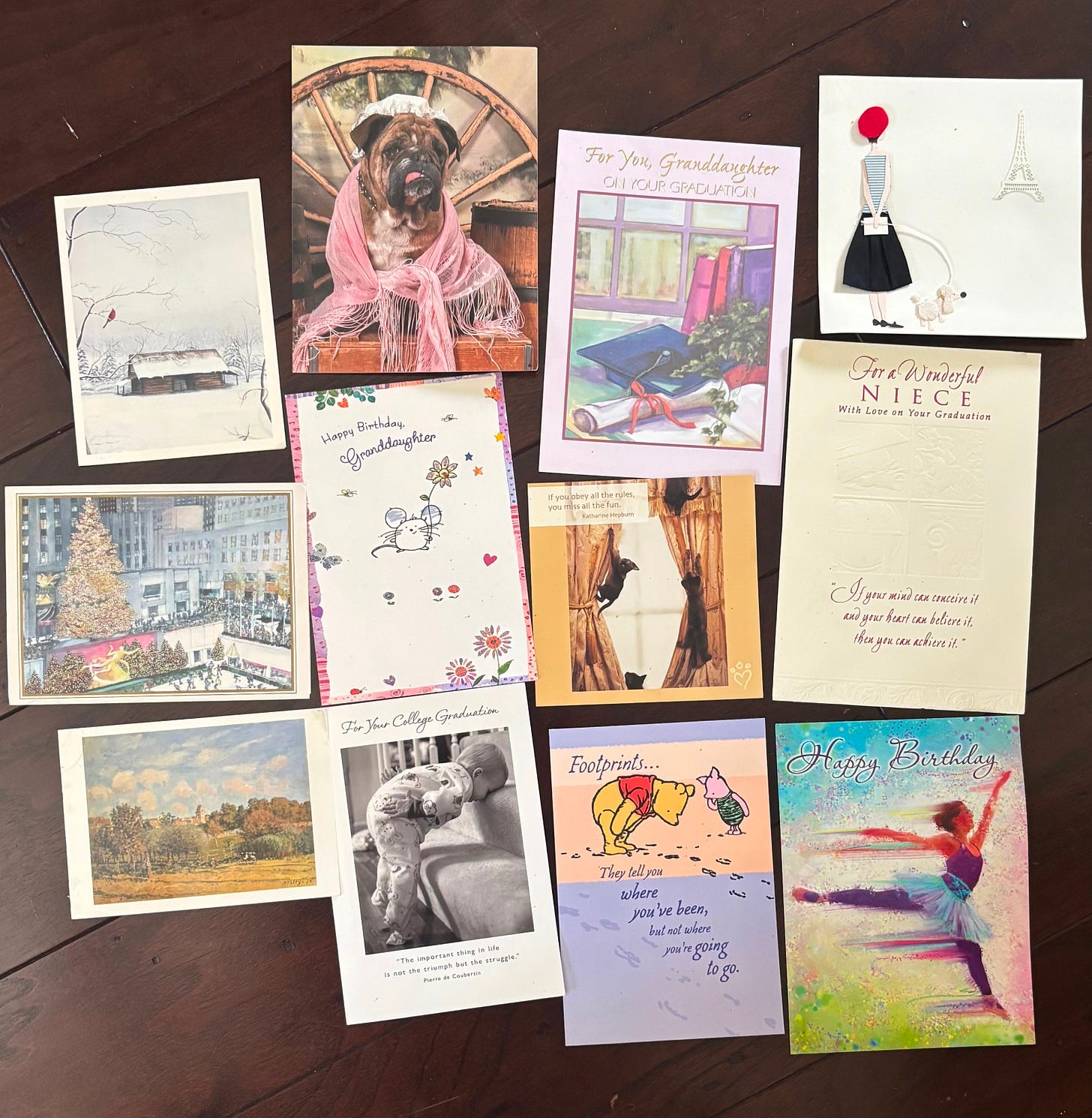

My grandmother Eleanor had kept dozens of Mother’s Day notes from her children, many of them carefully crafted by my aunt Linda, my father’s scrawling print signature added in under her neat script as an afterthought. She’d kept birthday and anniversary cards from my grandfather along with a few cards from her grandchildren.

Eleanor was the most practical and unsentimental about home. She shed houses like snake skins to improve the lives of the people she loved. She left New Jersey for Florida to make my grandfather more comfortable in his final years of life and as soon as he was dead and buried, she sold her Florida condo and moved back to New Jersey to be close to her oldest grandchildren. No sooner were those three grandkids off to college, she was back in the moving truck on her way back to Boca to be close to her youngest grandson. I was the only grandchild she never managed to live close to, so she settled for long car rides to ferry me between my parents’ houses when I was still too young to fly. In those many hours we spent together in her car, she taught me to count change, to sing the Mills Brothers, and to always say “Yes,” never “Yeah,” her critical contributions to practical education and good breeding.

And yet, as unsentimental as she was about her houses, she still left behind a “NEVER DESTROY” folio of the sentimental artifacts of a loving life she just couldn’t part with.

Human memory is strange and faulty. The collage of a lifetime of memories preserves the standout moments and obscures those worth forgetting, interspersed with the crucible trial moments that shape a life.

I’ve always felt some kind of hole in my soul, the acid-wash of transience. I’ve yearned for home, searched for it in unlikely places, and despaired at being unable to find it. I’ve learned to face the question “where are you from?” with a steely blend of resignation and resilience. In almost 40 years, I’ve never felt myself to be “from” anywhere.

But the Boca house was the closest thing I had to a “home.” At some point in the last two decades, the house my father and stepmother built became a living vessel of my life choices.

I finally found the box of my own regalia in a corner of the garage, crushed under a box of books ready for donation. Perhaps it had been moved during my stepmother’s exit and never found its way back to my room? I dragged it upstairs and unloaded its contents: a prom mug from 2002, photos and ripped CDs from my college boyfriend, play programs I didn’t remember, along with sports medals without an insignia to suggest when they were granted.

Having just perused my grandmother’s NEVER DESTROY file, I felt more sentimental about which cards to keep and which to recycle. I could no longer free-ride on my father’s closet space, so anything I kept, I’d have to find space to maintain.

Finally, satisfied that I’d discarded everything I could part with, I carefully placed all the objects for safekeeping in a new moving box and headed to the airport. Maybe circumstance will call me back one last time before the house is listed and sold. Maybe they won’t. I said a silent goodbye like it was the last time.

It’s time for me to find my own center, to keep my own file folder, to be my own port in the storm. I hope this is one small step toward finding home.

What does “home” mean to you?

When my parents sold the house I grew up in, I didn’t think much of it until one night I woke up in the middle of the night with a sense of that house as a living creature who had nurtured me. I cried SO hard from a deep place inside me, wrote a goodbye / thank you letter to the house, and drove down there the next day to bury it in the backyard. I think “New Hampshire” will always be home to me, but also Boston, Ireland, mountains generally. I lug it around with me in keepsakes, too. Photos are precious, and old art.

Timely post for me as I just revisited the storage space I rented when I left LA two years ago for the first time. When I got there one of my boxes of keepsakes — letters and cards from loved ones, concert tickets, pictures, etc. — literally fell out on me when I opened the door. I am not generally a nostalgic person and don't often revisit this stuff, so it was a surprise to read through them and have my heart thoroughly squeezed. (My grandmother's handwriting!!) As a nomadic sort, I'm very much in a process of discovering what home is to me, and I am so glad there is a box of mementos somewhere, even if I don't want to open it very often.